This is the tale of the Mercedes-Benz 190E 2.3 16 and 2.5 16 sport sedans. Developed in collaboration with Cosworth initially for the rally scene of the 1980s, the flagship version of the 190E series eventually went on to dominate track-racing and ended up on the roads as well, putting up a good fight against BMW‘s iconic M3. Even though nine times out of ten, people would choose the Bimmer over the Merc, the 190E Cosworth’s underdog status makes it an equally appealing car. As Richard Hammond put it: “it was Cinderella, but the coach never came”.

But let’s take it from the start. In the late ’70s, the V8-powered 450SLC rally car started to show the signs of aging, so the Stuttgart automaker decided to replace it with a compact model. Jointly developed with Cosworth, the 190E never made to rallying though, as Audi took everyone by surprise with the Quattro, featuring four-wheel drive and a turbocharged engine. Mercedes’ management didn’t want to fight an battle it couldn’t win so instead, they competed in the German Touring Car Championship (DTM).

But let’s take it from the start. In the late ’70s, the V8-powered 450SLC rally car started to show the signs of aging, so the Stuttgart automaker decided to replace it with a compact model. Jointly developed with Cosworth, the 190E never made to rallying though, as Audi took everyone by surprise with the Quattro, featuring four-wheel drive and a turbocharged engine. Mercedes’ management didn’t want to fight an battle it couldn’t win so instead, they competed in the German Touring Car Championship (DTM).

Motorsport regulations stated that, in order for a racecar to be homologated, there had to be a road-going version. So, at the 1983 Frankfurt Motor Show, Mercedes unveiled the 190E 2.3-16 Cosworth. It couldn’t have been a more better time for this, as, just one month earlier, three Cosworth prototypes set a number of world speed records at the Nardo (Italy) oval, after being driven non-stop for over 50,000 km (31,069 miles).

According to the plan, the distance was to be covered in 8 days, at an average speed of 240 km/h (149 mph). Six pilots drove in 2 and a half hour shifts and completed the task in exactly 201 hours, 39 minutes and 43 seconds.

More amazing was the fact that all three cars finished without breaking down, only needing routine maintenance and, of course, refueling.

The heart of the production 190E 2.3-16 was the four-cylinder Cosworth engine, based on the 136 hp 2.3-liter stock Mercedes powertrain. It was made from a light alloy, fitted with dual overhead camshafts and four valves per cylinder. The British engineers made the valves as large as they could be for the given displacement and also used a Bosch K-Jetronic injection system.

The 2.3-16 delivered 185 hp at 6,200 rpm and 240 Nm (177 lb-ft) at 4,500 rpm, easily revving up to the 7,000 rpm redline. It was pretty fast for its time reaching 100 km/h (62 mph) from standstill in 7.5 seconds and a top speed of 230 km/h (143 mph). Due to stricter emission regulations, U.S.-spec models had a slightly weaker engine, rated at 167 hp and 220 Nm (162 lb-ft).

The power was sent to the rear wheels through a five-speed manual Getrag transmission with a racing gear pattern. That meant it had a “dog-leg” first gear, left and down from neutral. The steering ratio was shortened, for added precision, while the steering wheel itself had a smaller diameter.

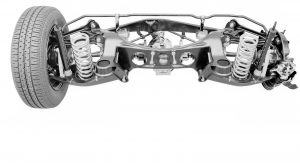

With a 0.32 drag coefficient, the 190E Cosworth set a new world record for the time. It was also a car that showcased many advanced engineering solutions, such as an electronically controlled limited-slip differential (LSD) and self-leveling hydraulic suspension on the rear axle.

Inside, leather-clad Recaro sports seats provided ample support during fast cornering, alongside the aggressively shaped rear bench, while the instrument panel had additional gauges – oil temperature, voltmeter and stop watch.

Only two exterior colors were available, the Blue-Black metallic and Smoke Silver.

In 1984, driving a 190E Cosworth, Ayrton Senna, a relatively unknown driver at the time, won the first race held on the shortened Nürburgring, signaling the birth of two very big stars.

But the 2.3-16 was just the beginning of the 190E Cosworth saga. In 1988, a new model followed, the 2.5-16. It had a bigger, 2.5-liter engine, delivering ten more ponies, for a total of 195 hp. There were also cars without catalytic converters, capable of 204 hp. Two new exterior colors were offered, the Almandine Red and Astral Silver. Overall, the 2.5-16 wasn’t a quantum leap, but it did help the 190E Cosworth to keep up with its arch nemesis, the E30 BMW M3.

Until 1988, the 2.3-16 was raced in different touring car championships by privately owned race teams. When Mercedes officially entered DTM, a new road going version was needed for homologation. This is how the 2.5-16 Evo I limited edition came to be.

Only 502 units were built, featuring the same 2.5-liter 195 hp engine, with slight modifications. The powertrain had a shorter stroke and bigger bore, which allowed it to rev higher. Also, the rotating masses were lightened, lubrication improved and cam timing altered.

The running gear received the most important upgrades, being optimized for heavy track use, as more and more 190E Cosworth owners were entering weekend races.

For those wanting more performance, Mercedes also offered a DM18,000 PowerPack developed by AMG, delivering 30 extra horsepower. The upgrade included different camshafts, larger throttle body and more aggressive engine management. The intake and exhaust systems were optimized as well.

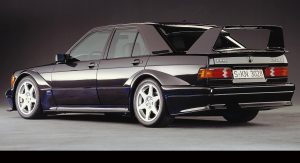

The 1990 Geneva Auto Show saw the introduction of the Evo II, the most capable of all 190E Cosworths.

This time the engine was considerably more powerful, churning out 235 hp and 245 Nm (181 lb-ft) of torque, the latter constant between 5,000-6,000 rpm. Tipping the scales at just 1,300 kg (2,866 lbs), the Evo II could accelerate from 0 to 100 km/h (62 mph) in 7.1 seconds and reach a top speed of 250 km/h (155 mph) – impressive figures back then.

The Evo II had an adjustable sports suspension, with three height levels, operated by a switch placed to the left of the steering wheel. Front passengers were given even more aggressive sports seats, while the rear bench was configured for only two individuals.

An extensive bodykit, boasting an oversized rear win and blistered wheel arches, made the Evo II downright menacing and aerodynamically more efficient, with a drag coefficient of only 0.29.

The Evo II had a limited run of 502 units, 500 painted in black, while the last two were silver. Base price was DM115,260, approximately €58,932 in today’s currency. Granted, that was a lot, but, hey, good things are never cheap.

By Csaba Daradics

![Classic Flashback: Mercedes-Benz 190E 2.3 and 2.5 16v Cosworth [with Video]](https://www.carscoops.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/Mercedes190ECosworth0.jpg)