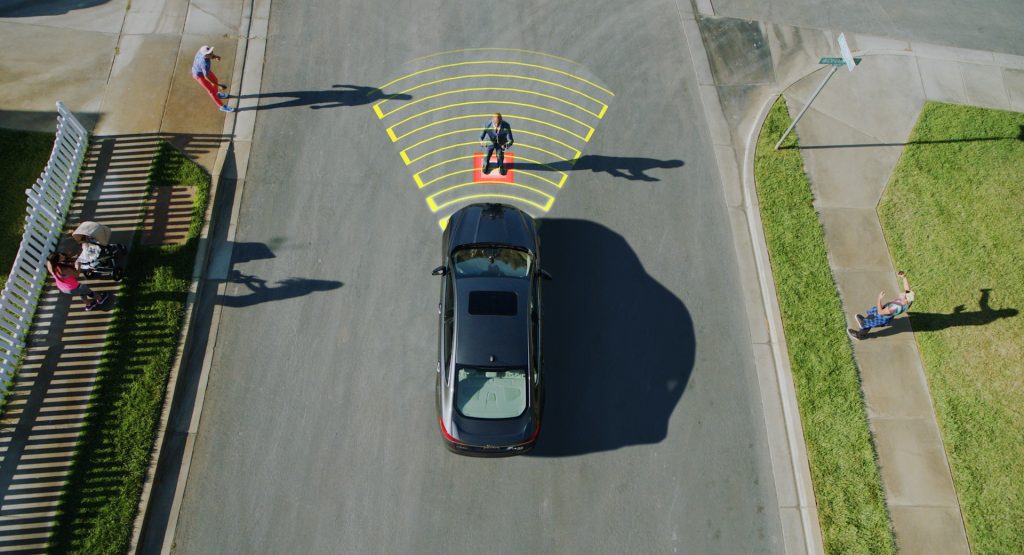

Vehicles equipped with automatic emergency braking systems that can detect pedestrians do prevent accidents and injuries, however, a new Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) study shows that they falter in areas with low light and high speed limits.

According to the study, which was authored by Jessica Cicchino, IIHS VP of research, the pedestrian alert systems reduced the likelihood of a crash by 27 percent overall, and by 30 percent for accidents with injuries, which the study notes is a success for the systems.

When the IIHS looked only at real-world pedestrian collisions that occurred at night on roads with no street lights, it found that the crash avoidance technology made no difference at all. Similarly, on roads where the speed limit was higher than 50 mph (80 km/h) or when a vehicle was turning, the technologies had no impact, showing that advanced driver assistance systems can struggle in adverse conditions.

Read Also: IIHS Will Tackle Misuse Of Advanced Driver Assistance Systems With New Rating System

“This is the first real-world study of pedestrian [automatic emergency braking] to cover a broad range of manufacturers, and it proves the technology is eliminating crashes,” said Cicchino, in a statement. “Unfortunately, it also shows these systems are much less effective in the dark, where three-quarters of fatal pedestrian crashes happen.”

Sadly, the technology is needed now more than ever. Pedestrian deaths have risen 51 percent since 2009, per the IIHS. It adds that the 6,205 pedestrians killed in 2019 accounted for almost a fifth of all traffic fatalities. That same year, around 76,000 pedestrians suffered non-fatal injuries.

As a result, the institute is developing a nighttime test and plans to publish the first official nighttime pedestrian crash prevention ratings later this year.

“The daylight test has helped drive the adoption of this technology,” says David Aylor, manager of active safety testing at IIHS. “But the goal of our ratings is always to address as many real-world injuries and fatalities as possible—and that means we need to test these systems at night.”

When the IIHS first made vehicle-to-pedestrian front crash prevention a requirement to earn its highest safety ratings in 2019, just three out of five of the vehicles it tested were available with the technology. Now it’s available in nine out of 10 vehicles and nearly half earned its “superior” rating.

Already, though, the IIHS has revealed some preliminary results of its nighttime testing and they’re promising. Although almost all of the vehicles it tested performed worse in the nighttime test than they did in the daytime test, the best systems combined cameras and radar and were not available in 2019, when the data from this real-world study were collected.

“This may indicate that some manufacturers are already improving the nighttime performance of their pedestrian AEB systems,” said Aylor.